RXJ0911+0551 is another excellent example of a multiple quasar system described as a gravitational lens by astronomers and astrophysicists. As with my previous two examples, the Einstein Cross and PG1115+80, this system consists of four high redshift quasars encircling a lower redshift central galaxy. In SIMBAD the quasars are listed as a single object QSO B0908+0603 and the central galaxy is listed as [KCH2000] L2. QSO B0908+0603 is listed as having a redshift of 2.7933 z which supposedly places it at a distance of 11.5 billion light years using a so-called Hubble Constant value of 70 (km/s)/Mpc. [KCH2000] L2 is listed as having a redshift of 0.7689 z which supposedly places it at a distance of 6.8 billion light years from Earth also using a so-called Hubble Constant value of 70 (km/s)/Mpc. However, despite being allegedly separated by a distance of almost five billion light years, filaments of material can be seen connecting the central galaxy with the surrounding quasars in this system.

|

|

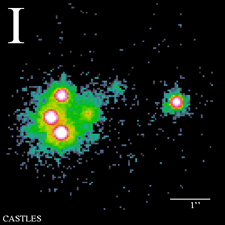

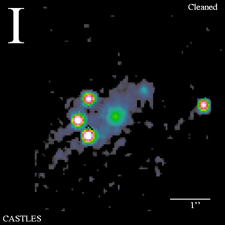

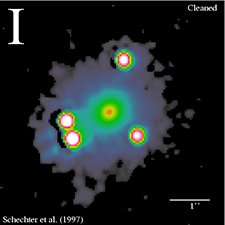

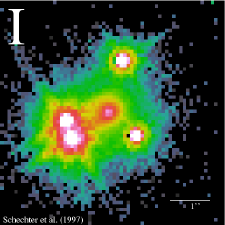

The above pair of images is from the CfA-Arizona Space Telescope LEns Survey (CASTLES) which utilized Hubble Space Telescope optical and near infrared images using NICMOS/NIC2 for H band observations and WFPC2/PC1 for V and I band images when none exist. The image on the right has been “cleaned” using image  filtering software based on hypothetical gravitational lens models. Yet the image still clearly shows faint streamers of material between the central galaxy and encircling quasars, but they are not mirrored as would be expected in a gravitational lens. The near-infrared image on the right is from the 2.56 m Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) using the High Resolution Adaptive Camera (HIRAC) and from the ESO 3.5 m New Technology Telescope (NTT) using the “Son of ISAAC” (SOFI) near-infrared camera. It shows a jet of material on both sides of the central galaxy with one jet connecting it with the lower left quasar in the system. But again nothing is mirrored as would be expected in a true gravitational lens.

filtering software based on hypothetical gravitational lens models. Yet the image still clearly shows faint streamers of material between the central galaxy and encircling quasars, but they are not mirrored as would be expected in a gravitational lens. The near-infrared image on the right is from the 2.56 m Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) using the High Resolution Adaptive Camera (HIRAC) and from the ESO 3.5 m New Technology Telescope (NTT) using the “Son of ISAAC” (SOFI) near-infrared camera. It shows a jet of material on both sides of the central galaxy with one jet connecting it with the lower left quasar in the system. But again nothing is mirrored as would be expected in a true gravitational lens.

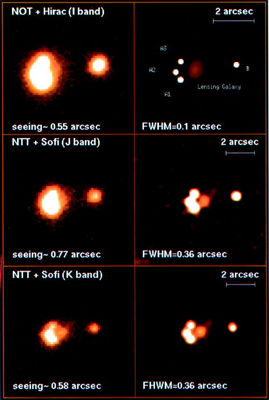

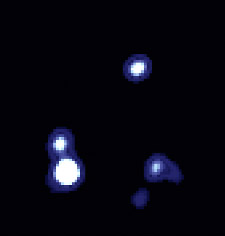

Astronomers have observed the x-ray fluctuations of the four quasars in RXJ0911+0551 in the hopes that a shared flare up between them would prove that they are merely mirages of the same background quasar. A sudden increase in x-ray intensity was detected using the Chandra X-ray Observatory. But the flare up, which lasted for more than half an hour, only occurred for one of the four quasars. Astronomers measured x-ray intensities of the four quasars for over eight hours but the flare up never repeated in any of the other three. The image below on the left is taken from the Chandra Press Room and shows the light curves of two of the quasars with the flare up clearly visible in one and not the other. Astronomers refused to give up and claimed that the flare ups of the other  quasars must have occurred before their observations were made. The astronomers also claimed that a long term observation of this system will reveal shared flare ups among the quasar “mirages” providing precise extragalactic measurements and thereby allowing the expansion rate of the universe to be better estimated. The original observations were made back in 2000 and despite all of these claims there have still yet to be any long term observations made of RXJ0911+0551.

quasars must have occurred before their observations were made. The astronomers also claimed that a long term observation of this system will reveal shared flare ups among the quasar “mirages” providing precise extragalactic measurements and thereby allowing the expansion rate of the universe to be better estimated. The original observations were made back in 2000 and despite all of these claims there have still yet to be any long term observations made of RXJ0911+0551.

Time and again scientists have tried to prove that this quadruple quasar system is a gravitational lens and time and again they have failed. It is interesting that multiple quasar systems contain a limited number of quasars encircling a central galaxy in a limited number of positions. What can account for this and for the bridges of material between these objects? As I speculated in my previous examples, perhaps this is due to the quasars being ejected from the central galaxy in a symmetrical tetrahedral pattern. An excellent way to visualize such a pattern is to look at a Jmol model of a methane molecule. I am not suggesting that methane plays any role in multiple quasar systems. But the four hydrogen atoms surrounding the carbon atom in a methane molecule can be rotated to very closely match the positions of the quasars in multiple quasar systems, including RXJ0911+0551 as shown in the image below on the right.

The reason that quasars ejected from a central galaxy could be positioned in such a way is simplicity. A tetrahedron has the least number of faces and angles of any geometric solid. The least number of objects, other than a pair, that can be evenly spaced with matching angles around another centralized object is four, but only if they are positioned at the vertices of an imaginary orthographically projected tetrahedron.

The reason that quasars ejected from a central galaxy could be positioned in such a way is simplicity. A tetrahedron has the least number of faces and angles of any geometric solid. The least number of objects, other than a pair, that can be evenly spaced with matching angles around another centralized object is four, but only if they are positioned at the vertices of an imaginary orthographically projected tetrahedron.

There are many more examples of tetrahedral symmetry displayed in compact multiple quasar systems, several of which I would like to post. But tell me readers, do you think this is a viable explanation for what has been reported as gravitational lensing in many systems? Or are there other alternatives that can better explain the number and positioning of quasars in these multiple quasar systems? Let me know and thanks for reading!

Shannon

The following image on the left is from the CfA-Arizona Space Telescope LEns Survey (

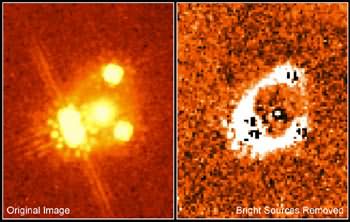

The following image on the left is from the CfA-Arizona Space Telescope LEns Survey ( Despite this evidence there are still scientists who try to manipulate the data. The pair of infrared images on the left is taken from the Hubble Space Telescope NICMOS. The left image is the original while the right image has supposedly had the quasars and central galaxy digitally subtracted from it to reveal a lensed galaxy in the background. There are a few problems with this processed image however. Besides the dubious method of subtraction used to create the image, the resulting ring of light is incomplete and irregularly shaped and does not conform to any accepted

Despite this evidence there are still scientists who try to manipulate the data. The pair of infrared images on the left is taken from the Hubble Space Telescope NICMOS. The left image is the original while the right image has supposedly had the quasars and central galaxy digitally subtracted from it to reveal a lensed galaxy in the background. There are a few problems with this processed image however. Besides the dubious method of subtraction used to create the image, the resulting ring of light is incomplete and irregularly shaped and does not conform to any accepted  optical physics or gravitational lens models. The image to the right is a 7+ hour exposure of PG1115+080 made by the

optical physics or gravitational lens models. The image to the right is a 7+ hour exposure of PG1115+080 made by the  The best way to view these alignments is to utilize a Java applet such as

The best way to view these alignments is to utilize a Java applet such as